What is Risk in Investing?

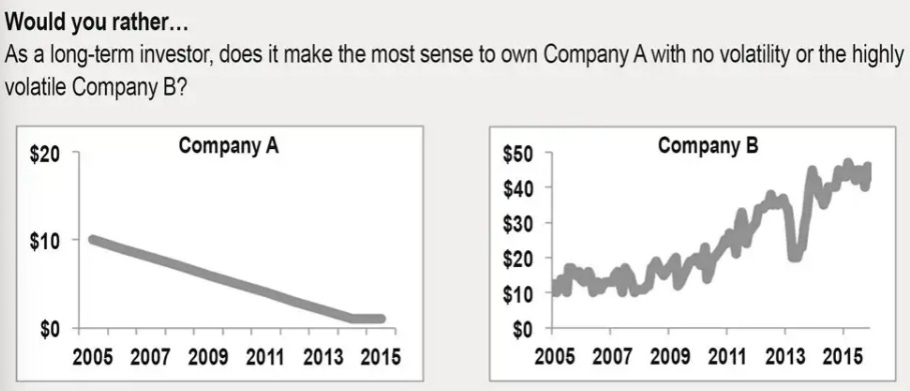

Risk is often thought by many in the finance world to be closely tied to an asset’s volatility. In the short term, volatility can impact a portfolio but does it matter to long-term investors?

Risk is often thought by many in the finance world to be closely tied to an asset’s volatility. In the short term, volatility can impact a portfolio but does it matter to long-term investors? I don’t think it does, volatility is simply a measure of how much an asset’s price fluctuates.

But if so, then why is it still used to measure risk? Founder of Oaktree Capital and world-famous investor, Howard Marks, believes it’s largely because volatility can be reduced down to something easily measurable. This makes it easier to work with and means it’s simple for money managers to explain an asset’s risk to clients.

So it’s useful to money managers, but here’s the key to seeing the problem with it: If you use volatility to measure risk and a company’s share price goes down, despite nothing in the underlying business changing, the company is seen as more risky.

Put like this, it seems so stupid it’s hard to fathom anyone actually believing it.

If the price of anything else went down for no reason, you’d have to be crazy to think it’s a riskier investment. Common sense should dictate that the asset becomes more attractive if it’s selling for a lower price. If you were buying a house and the seller suddenly decided they wanted to cut the price from $500,000 to $250,000 for no reason, you’d think it was great news. So why isn’t it the same when investing in stocks?

Of course, there are plenty of examples of volatility preceding a market collapse, some of the most famous ones include:

The .com bubble where the Nasdaq rose 800% from 1995 to March 2000, only to fall 78% by October 2022.

The Japanese stock market crash in the late 80s and early 90s where the 1.15 square kilometer Tokyo Imperial Palace grounds were thought to be worth more than the whole of California.

And even further back in history when tulip mania gripped Holland, peaking in 1634 - 1637. The price of tulips rose to roughly the same as the price of a mansion along the Amsterdam Grand Canal, before crashing in just a few months to the value of nothing.

But these examples of extreme volatility all have one thing in common - the underlying asset was clearly way overvalued. A tulip bulb should never be valued at anything like the price of a house. Maybe volatility is an effective measure of how extreme a market has become, but it’s no measure of the likelihood of losing money in an investment.

Extreme volatility in the market is more a sign of emotions taking over and investors failing to act rationally. Famous economist, John Maynard Keynes, coined the term animal spirits in 1936, to refer to a type of behaviour where rationality retreats and emotions start to take over.

When a stock price goes up or down by 5% in a single day, if nothing in the underlying business has changed, it’s an emotional reaction from investors (or nowadays, an algorithm-driven reaction) rather than a rational re-valuation of the stock.

Yet despite volatility widely being acknowledged as a poor measure of risk by most of the successful and famous investors, it’s still used by institutions and even retail investment platforms.

But if volatility shouldn’t be used to measure risk, what should?

What Should Be Used to Measure Risk?

I’ve seen an interview with Warren Buffet where, to paraphrase, he says: risk in investing is the probability of losing money on an investment. Unfortunately for quants and hedge funds, this is a lot harder to quantify than volatility.

So how could we try to measure the probability of losing money on an investment? Firstly, it’s important to realize that there’s always some amount of risk with any investment. Even keeping cash in the bank is risky as there’s always a chance the bank will go under.

Holding cash is arguably the most risky investment you can make as it’s the only way you’re virtually guaranteed to lose money - inflation will make sure that your cash loses a little (or a lot) of its buying power each year.

Buffet also said, “risk comes from not knowing what you are buying.” What he meant was that, although risk is inherent with every investment you make, there are ways to reduce it. To minimize the probability of losing money when investing, you have to understand the business and the industry.

This might take weeks or even months of research but it’s important to do if you want to maximize the chance of making a good investment.

In a broader sense, this isn’t only applicable to finance, it applies to many aspects of life. The more you research something before making the final decision, in theory at least, the lower the chance you’ll make a poor decision. Just don’t get stuck in analysis paralysis.

To me, the best way to define investing risk is “the probability of losing money”. But unfortunately, as we saw above, it’s much harder to define or quantify than simply using volatility. If it was easier to measure, many more investors would outperform the market.

Perhaps investors just have to accept that there is no easy way to measure risk, and at the end of the day, the precise risk of investing in any asset is ultimately unknowable.

Takeaways

Using volatility to measure long-term risk is dumb. If the price of something goes down, and nothing in the underlying business has changed, it’s not a more risky investment, it should be more attractive.

Using volatility as a measure of risk also makes it feel like lowering your risk level is out of your control. You can’t control the volatility of an asset and if you believe the above, you therefore can’t control the amount of risk you take in an investment.

Volatility is only used as a measure of risk because it’s easy for asset managers to quantify. A better measure of risk would be the probability of losing money, unfortunately, this is impossible to quantify precisely.

But there are ways to lower your long-term risk of losing money. Mainly researching and understanding the business and industry you invest in.

This is a great point that highlights the importance of focusing on things within your control, like doing research on a company, rather than freaking out because the market tanked. As long as you know what you hold, you should be comfortable holding or buying more when the price drops, given that the fundamentals have not changed.

Nice work Harry 💸